The Colony of Kent

The Colony of Kent

The failed Colony of Kent is a fascinating part of the Woods’ story. It was here, we believe, that they meant to settle. We are basing this on a couple of bits of information. One, Lt. (or Capt.) Charles Finch MacKenzie was in charge of leading their group of settlers. The Colony of Kent articles included here both indicate that MacKenzie was still engaged with that endeavor when the Woods arrived in the spring of 1851. Also, the Wood family were taken to Fort Graham, very near the site of the failing/failed colony.

The news article below by John Banta indicated that “within a year” the colony of Kent had failed. Banta also mentions a corn crop and corn would not have been planted until just before the Wood family’s arrival. There was a drought that year and I would imagine the crops were in bad shape. But Wood and their company would have arrived after that crop had been planted and well before harvest time. I don’t know when the horses Banta mentioned ate the corn crop, but the corn would have to have been planted and growing in order for the horse to eat it. Seems to me that this would have happened after the Wood’s arrival. Which means that while the colony was probably mismanaged and the colonist disgruntled (see the Banta article below), it hadn’t completely failed yet.

Banta writes about the increasing Indian raids. To newly arrived Scottish immigrants, that was probably frightening and at odds with what was told to them by George Catlin and others. They were sick, weak, tired, sad, and scared. I can’t imagine what Texas in a full on drought with hostile natives looked like to these newly arrived folks from Ayrshire.

Our family history says that James and Isabella arrived and found out that they had been swindled and had to find another piece of property. Isabella wrote a letter upon their arrival back to Scotland describing their journey. That letter can be read here. A letter written to James by his brother, Hugh in April 1852 mentions a few things that shed light on the situation. One, Hugh proclaims the Colony of Kent to be failed. Two, he talks about James’ options. Hugh mentions a return to Scotland, relocating to another “older state” like Illinois, or finding a different property in Texas. Later in the letter, Hugh also discussed with James that he (James) would be able to petition Sir Edward Belcher to return his money once Belcher returned from South America. From this we know that Kent is defunct. Belcher is returning money to the settlers. James is absolutely not going to settle in Kent and was looking at other options.

Hugh also mentioned that he desired for James to find a safe place to live where he and his family could be prosperous and safe from Indian attacks. Banta also mentioned the increasing attacks on settlers by the native population. What is interesting is that Fort Graham was closed in 1853 because the frontier had moved further west and there was no threat of Indian raids on settlers. That doesn’t seem to be the case. James and Isabella may have chosen to remain at Fort Graham for safety’s sake and in doing so, felt they had time to make a decision.

In either case, the land with the added danger of Native Americans and the failing of the Colony of Kent made James Wood decide to look elsewhere. The family eventually purchased the land survey and home of Elisha Smith Wyman. This home was also in a remote location, but the semi-nearby settlement of Milford had enough people in the area that they were able to incorporate in 1853.

There is an excellent article in the Texas Handbook Online about the Colony of Kent. You can click here to read that entry.

The following article appeared in the Waco Sunday Tribune-Herald newspaper on August 15, 1982. It was written by John Banta.

A Forgotten Dream

Tragic memories only remains of early-day colony of Kent

By John Banta

Central Texas is full of ghost towns, places that were once ambitious communities but which died, leaving little more than a heap of stones and a few dim memories.

The City of Kent, whose founders had glowing hopes that it would become another Cincinnati or Pittsburgh, died with a year of its birth. It left no pile of stones, not a trace of physical evidence that it ever existed. But it left many memories, most of them of hardship, tragedy and death.

In the fall of 1850 about 200 middle class people left England to found a city in Central Texas. They brought with them delicate china, linens and find brandies.

Among the colonists were the Rev. and Mrs. Richard Burton Pidcocke, their four sons and a 20-year-old-daughter, Isabella.

Leading the colonists was young Charles MacKenzie, a former officer in the British army, a bachelor.

During the voyage MacKenzie and Isabella Pidcocke began a shipboard romance, much to the dismay of Isabell’s parents, who wanted her to marry a distant but well-to-do cousin.

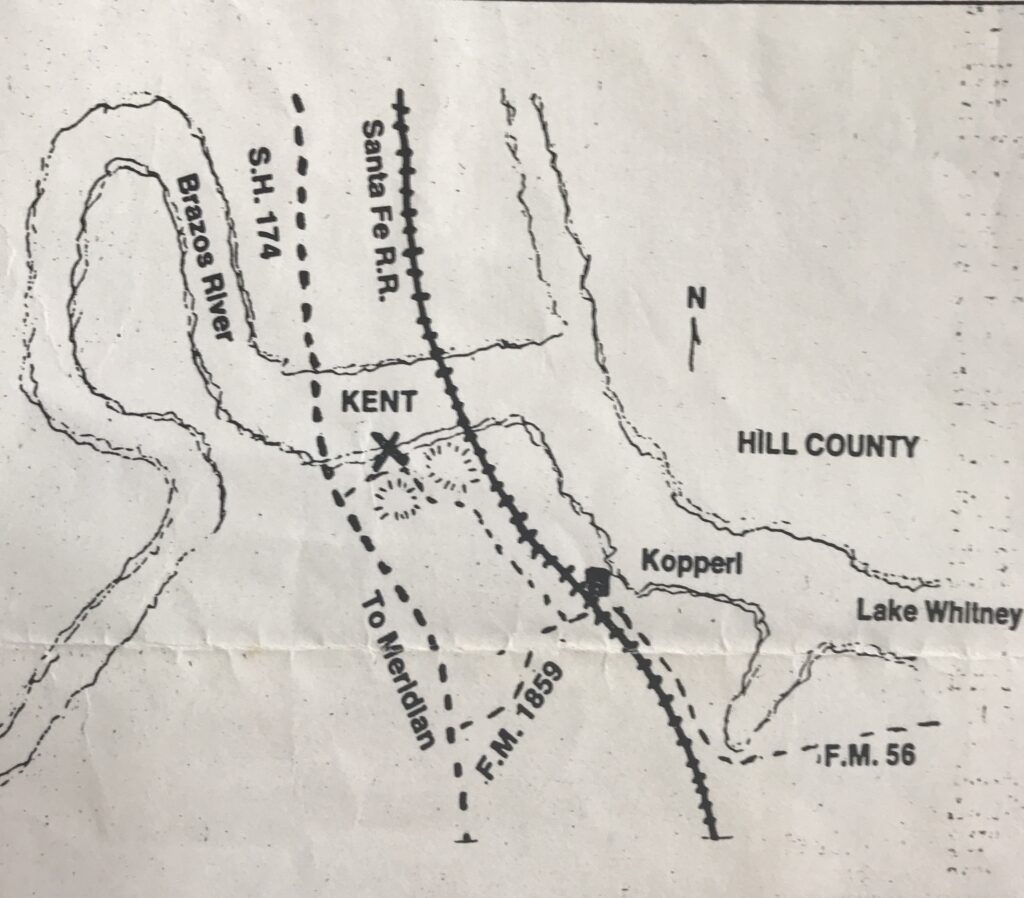

The colonists landed at Galveston. They sent their agent, Sir Edward Belcher, inland to inspect a proposed colony site on Cowhouse Creek, in what is now Coryell County. Belcher rejected the site because it was too hilly. Then he looked at a large tract on the west bank of the Brazos River near the spot where Highway 174 crosses the river today.

Belcher liked the Brazos site. It had a good soil. Nearby was a big bubbling spring. Only a few miles away was Fort Graham and an army garrison that could protect the settlers from raiding Indians.

But the biggest attraction of all was the Brazos River itself. Belcher – incorrectly – believed that the Brazos was navigable all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, and he planned to base the colony’s economy on both agriculture and industry, shipping goods and produce down the river to the Gulf of Mexico, then to the great market places of the world.

Belcher bought 27,000 acres of the land from New York lad speculator Richard B. Kimball through Kimball’s agent, famed Texas land dealer Jacob De Cordova.

Once the land deal was complete, the settlers began the long overland trek from Galveston. It was winter. Texas northers chilled them to the bone. Rains flooded streams, making them impassable for days.

But despite the cold and rain, the romance between Isabella and MacKenzie grew warmer. By the time the colonists reached Cameron, he had proposed marriage and she had accepted. Apparently, the elder Pidcockes had weakened in their opposition to the romance because the Rev. Pidcocke performed the ceremony himself.

The settlers passed through the newly established Waco Village and moved on up to what the Rev. Pidcocke called “the promise land.” Maj. George Erath and Neil McLennan, two Waco surveyors who had laid off the Waco town site, surveyed the streets and lots for the new colony.

It was called the City of Kent.

The settlers tried to plant crops but failed. They were not used to the physical labor of farming. A fast-talking Texas horse trader came along and sold them more mules and horses than they could ever have used. The settlers turned the animals out to graze on open range. But instead, the horses and mules go into an unfenced 100-acre corn field and destroyed it. There were other disasters of this nature.

Young MacKenzie tried to run the colony like a military outfit, having the men fall out in formation and march off to work each morning. He was accompanied about the colony by his valet, who carried his gun for him.

Living conditions were wretched. Many of the people lived in huts woven from willow branches and plastered with mud. Others lived in dugouts. Many died. Then the army began to pull troops out of Fort Graham, and Indian raids became frequent.

Within a year the City of Kent was empty. The land reverted back to Kimball under terms of the original sale. Many settlers went back to England, while others moved to Waco and other communities over Central Texas. Some of their descendants are still here.

Charles MacKenzie and his bride returned to England, and he rejoined the British army to fight in the Crimean War. When the Civil War began in this country, they came back to America. He joined the Union army, was wounded and died on December 7, 1863. Isabella returned to England and died two years later.

The Rev. and Mrs. Pidcocke and their four sons moved to Coryell County and established a ranch on Cowhouse Creek near the site originally planned for the colony. The little town of Pidcoke, midway between Gatesville and Copperas Cove, is named for the family by leaves out the second “c” in spelling.

The elder Pidcockes died and were buried in Fort Gates Cemetery. Years later their sons wanted to erect graver markers for them but could not find their graves. Instead, they had a stained glass window installed in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Waco in their memory.

The window is there today.

There is no marker at the site of the City of Kent.